Part II: A Revolution Within a Revolution — Women, War, and the Presence of the Military Wife

- Melissa

- Oct 25, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 21

Series: Emergence of the Military Wife: How Women on the Homefront and the Battlefront Shaped the American Revolution

Author’s Note: Continuing from “Revolution at Home — How Enlightenment Ideals Empowered Women.” Part II explores how those Enlightenment sparks ignited real revolutions for women — from the parlor to the battlefield. I use ‘military wife’ as an analytical category to describe women structurally embedded in military institutions—not as a contemporaneous self-identity.

America in Crisis: The Age of Upheaval

As to the history of the revolution, my ideas may be peculiar, perhaps singular. What do we mean by the revolution? The war? That was no part of the revolution; it was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was affected from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years, before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington. — John Adams

Before the first shots at Lexington, the Revolution was already underway — in the minds and hearts of the colonists.

Between 1760 and 1775, economic strain, imperial arrogance, and Enlightenment ideas collided. The collision ignited the first successful transoceanic rebellion by a European colony against its empire.

When the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, a movement for rights became a war for nationhood. Yet the thirteen colonies were a fragile alliance — divided in culture, class, and loyalty — struggling to forge unity under the pressure of empire.

The Continental Army, formed in 1775, embodied that experiment in national identity. About 250,000 men — including 5,000 African Americans — served during the eight-year conflict. (However, many African Americans sought freedom by joining the British, lured by Lord Dunmore’s 1775 proclamation.)

The army’s ranks were diverse — farmers, merchants, and artisans — improvising their way toward independence.

Despite hardships and short enlistments, they forged a national identity rooted not in bloodlines but in sacrifice.

Redefining Patriotism: Women, Revolution, and the Politics of Courage

The war raised once again the old question of whether a woman could be a patriot— that is, an essentially political person— and it also raised the question of what form female patriotism might take. — Linda K. Kerber

The Enlightenment challenged kings, and women challenged the limits of citizenship.

Historians Harriet Branson Applewhite and Darline Gay Levy reveal how the Revolution sparked new political consciousness among women. From Boston’s protest circles to Abigail Adams, who famously urged her husband to “remember the ladies,” women began to see patriotism as both personal and political. (Oh, there is so much more to Abigail's quote, and I can't wait to write about it!)

Women led boycotts, wrote petitions, and raised funds — reshaping civic virtue into something domestic and defiant.

Women like Hannah Griffitts, Esther de Berdt Reed, Martha Washington, and many more, whom I will discuss throughout this blog, turned writing and organizing into acts of rebellion.

Phillis Wheatley (not a military wife), an enslaved woman but unbroken individual, published poetry that defined liberty as both political and spiritual freedom — proving that intellect could be revolutionary.

Their efforts expanded patriotism beyond the battlefield. It became a moral compass that encompassed quills, kitchens, and quiet (and not-so-quiet) acts of resistance.

Women’s Roles in the Revolution

While men fought in the fields, women kept the cause alive at home, in camps, and on the battlefield.

Camp followers — wives, mothers, and widows — were the army’s often unseen lifeline. They cooked, washed, nursed, and mended, doing the unglamorous work that not only kept soldiers active but also gave some women jobs and a sense of patriotism. (Women had followed armies long before 1775; this was not a new issue. What changed during the Revolution was the scale, documentation, and national-level administration of their presence.)

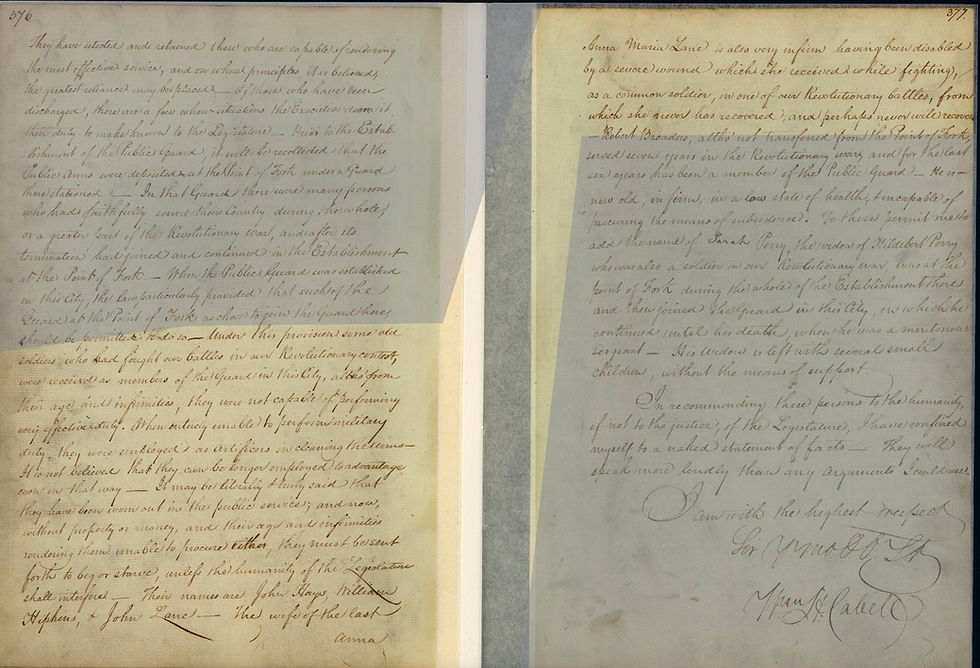

Even Martha Washington endured brutal winters in military encampments, serving as a stabilizing presence for both her husband and his men. She wasn’t a “camp follower” in the enlisted sense (i.e., Margaret Cochran Corbin, Anna Maria Lane, Mary Ludwig Hays) but rather a symbolic and practical figure of endurance.

General George Washington, in 1777, was initially frustrated by the “multitude of women…are a clog upon every movement,” but later recognized their indispensability. Eventually, Washington issued an order on September 8th, 1782, in which he often handled the camp followers differently from the active duty. He ordered officers to communicate directives directly to them "serjeants of the companys" to "communicate all orders of that nature to them"— a quiet acknowledgment that women were part of the military ecosystem.

Eventually, we gain insight into Washington’s mindset shift (who always wanted his wife by his side during winter encampments), as a letter (29 January 1783) to Robert Morris reveals that the wives of army enlistees were a significant morale issue for Washington.

The Cries of the Women—the sufferings of their children—and the complaints of the Husbands would admit of no alternative. The latter with too much justice remarked "If pay is withheld from us, and Provisions from our Wives & Children we must all starve together; or commit Acts which may involve us in ruin"—Our Wives add they "could earn their Rations, but the Soldier—nay the officer—for whom they wash has nought to pay them." In a word, I was obliged to give Provisions to the extra women in these Regiments or lose by Desertion—perhaps to the Enemy—some of the oldest and best Soldiers in the Service.

Washington issued an order on September 8th, 1782, in which he often handled the camp followers differently from the active duty. He expressed a desire to acquaint women with "serjeants of the companys" to "communicate all orders of that nature to them."

As there are many orders for checking irregularities with which the women, as followers of the army, ought to be acquainted, the serjeants of the companys to which any women belong, are to communicate all orders of that nature to them, and are to be responsible for neglecting so to do.

Women's (many of whom may have been enlisted military wives) fortitude transformed encampments into communities. These women proved that freedom wasn’t won by soldiers alone — it was sustained by everyone who believed in it.

A Revolution Within the Revolution

The Revolution promised liberty but delivered it unevenly. Still, for many women, it opened doors that could never be fully closed again.

In 1774, the Ladies of Edenton in North Carolina, founded and organized by a (possibly a military wife) named Penelope Padgett Hodgson Craven Barker, signed a public petition pledging to boycott British imports — a bold move that declared “the happiness of our country” was also their concern. Historian Danelle Gagliardi notes that wartime necessity turned domestic responsibility into civic action, pushing women from private life into public identity.

They managed families, ran businesses, and organized relief — discovering political agency in the process.

Yes, patriarchy lingered. So did slavery — shadowing every promise of liberty. But women, in all their complexity, lived the Revolution not as footnotes, but as fierce, feeling participants. Their stories twisted through race, region, and status: enslaved women and free women of color moved through shifting sands of power and false freedom, their very bodies negotiating liberty’s unfinished script. (More on that soon.)

Urban streets hummed with rebellion, while rural homes bore quieter revolutions. Yet in every crevice of this fractured freedom, women found space — and made it sacred. They rose as thinkers, as voices, as warriors behind the lines. And perhaps most enduringly, as military wives who carried the Revolution not just in banners, but in their burdens.

They weren’t merely part of the story. They were its pulse!

Their courage fulfilled Paine’s radical hope:

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

The Revolution did not invent military families, but it made their structural entanglement with army governance visible at a national scale. For many of these women and military wives, that new world began not on the battlefield but at home — where survival itself became a revolutionary act.

Documenting 250 Years of Military Spouse History

Within the Continental Army, the survival of soldiers’ families became a matter of military administration. Once family subsistence was tied to retention and morale, domestic life could no longer be treated as separate from military function. With the war’s conclusion, the presence of soldiers’ wives remained entangled with military structures in evolving ways. The administrative pattern made visible during the Revolution — linking family survival to military endurance — would recur in later American conflicts, as military spouses (men and women) continued to operate within systems that connected household stability to institutional effectiveness.

From camp tents to modern deployments, they’ve carried the same banner: Agency, influence, endurance, ingenuity, devotion.

They remain the quiet pillar of every fight for freedom in military history — then and now. Today’s military spouses carry the same mix of grit and purpose — showing that the legacy of Revolutionary women continues on the home front in every generation.

#MilitarySpouseHistory #HomefrontArchives #BehindTheUniforms #MilitaryWivesInHistory #AmericanRevolutionWomen #InstitutionalHomefront #LogisticsOfLiberty #MilitaryFamilySystems

Don't forget: On November 16, 2025, PBS will premiere The American Revolution, a new Ken Burns documentary reexamining the nation’s founding through untold perspectives—Burns looks at history from the bottom up, showing how the endurance of ordinary citizens also became the true test of patriotism.

Image Sources

Resolution Establishing a Continental Army and Appointing a Commander-in-Chief. Rough Journal of the Continental Congress, June 13–15, 1775. Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention. U.S. National Archives, 2024. Public domain.

Philip Dawe. A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina. London: Robert Sayer & J. Bennett, 1775. Mezzotint. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Public domain.

Phillis Wheatley. Frontispiece portrait from Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. London, 1773. Engraving attributed to Scipio Moorhead. Library of Congress. Public domain.

References and Sources

Applewhite, Harriet Branson, and Darline Gay Levy. Women and Politics in the Age of the Democratic Revolution. University of Michigan Press, 1990.

Adams, John, and Charles Francis Adams. The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: Life of John Adams. Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1856.

Ellet, Elizabeth Fries. The Women of the American Revolution, vol. 1. Williamstown, Mass: Corner House, 1980.

Ellet, Elizabeth Fries. The Women of the American Revolution, vol. 2. New York, NY: Baker and Scribner, 1848.

Garrett, Heather. “Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War.” History in the Making 9, no. 5 (January 2016).

Goldstone, Jack A. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World. University of California Press on Demand, 1991.

Hale, Sarah Josepha Buell. Woman’s Record: Or, Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from the Creation to A.D. 1868. Arranged in Four Eras. With Selections from Authoresses of Each Era, 2nd ed. 1860; repr., New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1860.

Harvard University. “Enlightenment and Revolution.” The Pluralism Project, 2024.

Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Moore, Lisa L., Joanna Brooks, and Caroline Wigginton. Transatlantic Feminisms in the Age of Revolutions. Oxford University Press, 2012.

O’Hara, Kieron. The Enlightenment: A Beginner’s Guide. Simon and Schuster, 2012.

Reed, Esther. The Sentiments of an American Woman. Philadelphia: John Dunlap, 1780.

Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections. “Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776.” Brandeis University, 2015.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: With Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. Project Gutenberg eBook, 2002.

Primary Source Documents

“*General Orders, 4 August 1777*.” https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0508. (Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 10, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr., Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000, pp. 496–497.)

“*General Orders, 8 September 1782*.” https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-09417. (Access document from The Papers of George Washington.)

“*From George Washington to Robert Morris, 29 January 1783*.” https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10529. (Access document from The Papers of George Washington.)

Comments