The First to Hurry Up and Wait: Martha Washington and the Beginning of a Long Tradition

- Melissa

- Jun 29

- 7 min read

Quiet Ranks: The Legacy of Military Spouses in American History – Part 1

A Legacy That Began Before the Nation

When we discuss military spouses in American history, we often focus on World War II, Vietnam, or the current all-volunteer force. But the story begins much earlier—with Martha Dandridge Curtis Washington.

Martha Washington: The “First” Military Wife

Yes, she was the wife of George Washington and the first First Lady. But before there was a presidency or a nation, she was a woman whose life changed dramatically when her husband was called to lead a revolution, not just a war, but a country.

We often remember Martha at Valley Forge—a resilient figure braving the cold beside her husband. But her journey into military life began much earlier. She had already endured personal losses, managed a vast estate, and navigated political change. By the time George was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in 1775... Martha had long been carrying weight that history rarely records.

(The loss of her first husband, managing an estate, and losing children.)

A Moment of Decision

When General Washington was named Commander-in-Chief, it gives me pause. I often find myself wondering how Mrs. Washington received such news. Was it conveyed by formal letter, hastily dispatched by courier? Or did they sit together days before in the quiet of their home, sharing tea and speaking of what might come? Had they contemplated the “what ifs”? Should war come, would he accept the burden of command? What words were spoken aloud—and what was unspoken between them?

Stepping Into the Unknown: At War and at Home

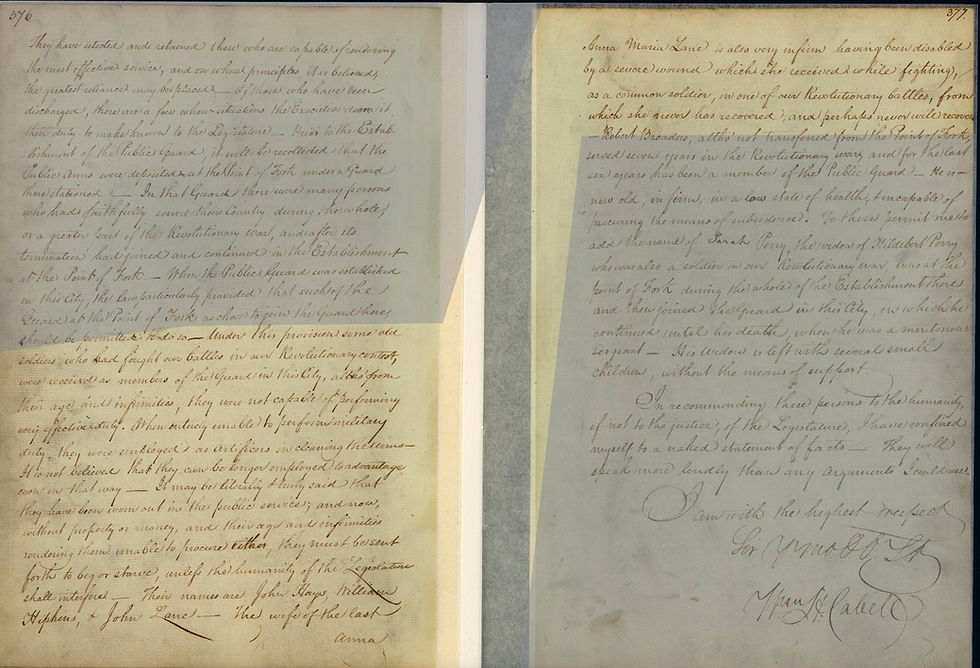

![Letter, George Washington to Martha Washington, June 18, 1775. Discovered tucked away in a desk drawer by one of Martha Washington’s granddaughters, this letter is one of two surviving letters written by George Washington to his wife just after he had accepted the Generalship of the Continental Army in June of 1775. [Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media and Mount Vernon.]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/9c2d76_4dc572aa6e504bff84ef35b343d6f87d~mv2.jpeg/v1/fill/w_600,h_473,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/9c2d76_4dc572aa6e504bff84ef35b343d6f87d~mv2.jpeg)

She received such a letter, not filled with battle plans, but heavy with consequences. Her husband had become the Commander-in-Chief of a fragile army. She did not know yet (or did she) that she had stepped into a role that military history hadn’t yet named.

During the Revolutionary War, Martha assumed responsibilities that went far beyond the typical duties of a wife. She traveled to military encampments during the winter, organized fundraising and supply efforts, and assisted in gathering clothing and provisions for the troops. By doing so, she not only managed her family life but also supported and funded George Washington, significantly contributing to the survival of the Continental Army.

A Legacy Entwined with Contradiction

![Mount Vernon 2024

[Photographer M.A.B]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/9c2d76_2a05b9271f7c4d2f88ef59892ea966d0~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_619,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/9c2d76_2a05b9271f7c4d2f88ef59892ea966d0~mv2.jpg)

And yet, she carried all of this while still managing the demands of her personal world: grief over the loss of her children, financial pressures, and the day-to-day

operations of Mount Vernon. Crucially, this included the brutal reality of overseeing enslaved people whose forced labor sustained the household and plantation. These individuals—so often written out of the narrative—were essential to Martha’s ability to carry out any of her public or private duties. Her legacy is complex– situated at the intersection of sacrifice, privilege, and historical contradiction.

It also raises curious questions: Who advised her? What community or counsel did she seek or rely on? What did she talk about with other military wives, such as Catherine “Kitty” Greene, Mercy Otis Warren, Catharine Van Rensselaer Schuyler, Esther deBerdt Reed, and several others? There were no spouse Facebook groups, no online forums, no military family handbooks—yet she had to build a network, formal and informal, that helped her and other wives to navigate it all.

Can you Image?

The Humanity Behind the History

And how did she feel? Was it pride or dread? Confidence or hesitation? That moment—reading a letter, hearing a knock at the door, saying goodbye—is deeply human. And in that humanity, Martha becomes not just a figure in portraits or textbooks, but a mirror to the millions who have since stood in similar shoes. Spouses who waited for letters (phone calls), watched news broadcasts, opened emails, and read DMs that changed everything.

There are endless biographies and archives about the Washingtons (OMG, I haven’t read them all), but I find myself drawn not to the grand narratives but the quieter, shared threads. Those that connect generations of military wives and spouses across centuries through shared feelings of uncertainty, loyalty, fear, absurdity, and unspoken strength.

More Than a Title:

A Lasting Blueprint

Martha Washington may not have known she was starting a tradition or creating a role, but in many ways, she did. She was the first First Lady, yes. But more than that, she was recognized as the "First" military wife to the Continental Army and to carry the invisible burden of being married to the mission… the war and the men come first, the country comes first. One of the first to embody the emotional labor, adaptability, and steady presence required of military spouses, then and now.

Her legacy reminds us that the roles, responsibilities, and grit of military spouses are not a new phenomenon– they’re hereditary. Her quiet strength, lived in private, but still echoes through the stories of those who stand by today’s service members, the mission and the wars.

Final Thought:

![It was produced around 1777 and is believed to be based on portraits of George and Martha by Charles Willson Peale that were painted in 1776 for John Hancock. Peale’s original portrait of Martha has been lost, but this engraving from it might provide an idea of what Martha looked like during the Revolution (image courtesy of the New York Public Library, C.W. McAlpin Collection). [Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media and Mount Vernon]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/9c2d76_3b69be31ce264d86b23735d240a949be~mv2.jpeg/v1/fill/w_600,h_401,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/9c2d76_3b69be31ce264d86b23735d240a949be~mv2.jpeg)

In Martha Washington’s steps, we hear them in today’s military spouses—those who serve without rank, wait without recognition, and hold families together through uncertainty. Martha may never have worn a uniform, but she helped shape a role and the fabric of military life, culture, and tradition and history long before it had a name.

I seriously doubt, Martha set out to define a role,(maybe an example) but her life became the blueprint. She is remembered as the first—and in choosing to stay, to serve, and to support, she became something more: the first to carry the quiet weight of war.

If we’re to truly understand the cost of conflict and the strength of a nation, we must look not only to those who lead armies but to those who stand beside the armies and the leaders. For American military spouses, that story began with 44-year-old, 5-foot Martha—when her husband, George Washington, became Commander-in-Chief of a fragile, first-ever Continental Army.

~Mel

Sources:

Carol Sue Humphrey, The Revolutionary Era: Primary Documents on Events from 1776 to 1800 (Greenwood, 2003).

Cokie Roberts, Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation, 1st ed. (2005; repr., ProQuest Ebook Central: Harper Collins, 2005).

Dorothy Auchter Mays, Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2004).

“George Washington to Martha Washington, 18 June 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0003. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 1, 16 June 1775 – 15 September 1775, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985, pp. 3–6.]

Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

Mary Beth Norton, Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800: With a New Preface (Cornell University Press, 1996).

Nancy K. Loane, Following the Drum: Women at the Valley Forge Encampment (2009; repr., Potomac books: U of Nebraska Press, 2009).

Sarah Josepha Buell Hale, Woman’s Record: Or, Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from the Creation to A. D. 1868. Arranged in Four Eras. With Selections from Authoresses of Each Era, 2nd ed. (1860; repr., New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1860).

Susan Casey, Women Heroes of the American Revolution: 20 Stories of Espionage, Sabotage, Defiance, and Rescue (Chicago Review Press, 2015).

Center for History and New Media. “About.” Martha Washington, https://marthawashington.us/

The Center for History, New Media at George Mason University. “At the Front.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2024. https://www.mountvernon.org

Images:

American Battlefield Trust. “‘First In Peace’ George Washington During 1783-1789.” https://www.battlefields.org.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “At the Front.” https://www.mountvernon.org

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “A Woman in Charge.” https://www.mountvernon.org

Hiller, Joseph, Sr., after Charles Willson Peale. Mezzotint, c. 1777. New York Public Library, C.W. McAlpin Collection. https://marthawashington.us

Joseph Hiller, Sr., after Charles Willson Peale, "Mezzotint, Martha Washington and George Washington," in Martha Washington, Item #226, https://marthawashington.us/items/show/226 (accessed April 6, 2021).

Letter, George Washington to Martha Washington, June 18, 1775. “Martha Washington.” https://marthawashington.us

William Francis Warden Fund, John H. and Ernestine A. Payne Fund, Commonwealth Cultural Preservation Trust. Jointly owned by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. https://collections.mfa.org

Comments