Breaking the Line: Margaret Corbin, a Military Wife, Steps Into History

- Melissa

- May 8

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 11

She didn’t wait for history to call—she fired first.

Margaret Cochran Corbin didn't wait to be remembered by history—she forced her way into it, cannon in hand. After her husband was killed in battle, she stepped forward to man his artillery position, voluntarily taking up arms. Her actions not only redefined expectations for women in wartime but also demonstrated how devotion—both for a cause and a spouse—could take the form of direct combat.

You might know her better by a more familiar, though collective, name:

Molly Pitcher.

Molly Pitcher” Was Never Just One Woman

A myth with many faces—and Margaret’s among the fiercest.

Historians have studied her extensively, footnoted, analyzed, and revisited more often than many of her male counterparts. The name “Molly Pitcher” is most famously linked to Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, but she was not the only woman behind the legend.

Much like Rosie the Riveter in World War II, “Molly Pitcher” became a symbolic identity—one name used to honor the courage and contributions of numerous women who stepped into the chaos of battle. Her enduring presence in American memory reminds us of the often-erased military roles women have played throughout history.

The myth may be collective, but the bravery was individual—and very real. McCauley deserves her own spotlight. Today, however, our focus is on Margaret.

Still Famous? Still Worth Telling

Even legends deserve a second look.

Skipping Margaret Corbin's story because she's "too well known" would be like ignoring Hamilton because there's too much singing. Even if her name rings familiar, let this be your introduction—or reintroduction—to one of the boldest figures of the Revolutionary War: Captain Molly.

“Pro-martyr among women in the cause of American Freedom, she is the symbol of conjugal devotion in time of fiery trial and an example of the self-sacrificing loyalty of the mothers of the Republic, without which Independence could not have been won.”

— Edward Hagaman Hall, 1932

Restoring Captain Molly: A Historian’s Crusade

Edward Hagaman Hall’s fight for justice, a century later.

In 1932, historian Edward H. Hall wrote a booklet for the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, attempting to clarify the confusion surrounding the identities of Margaret Corbin and Mary Ludwig Hayes and restore Margaret Corbin's rightful place in history.

He underscored Margaret's valor at the Battle of Fort Washington and contrasted her early heroism with a later life marked by injury, poverty, and neglect.

Hall believed that properly honoring her would correct a historical wrong—and bring

visibility to the countless Revolutionary women whose sacrifices went

unacknowledged.

One Woman, One Cannon, One Battle That Changed Everything

The siege of Fort Washington didn’t end with her wounds.

Margaret—or Margery—Corbin is remembered not only for her courage but for how her story faded into shadow, only to resurface through historical fragments. Portrayed as an Irish woman with a sharp tongue, fiery temperament, and a disheveled appearance—possibly shaped by poverty, trauma, and war—Margaret defied every norm of 18th-century womanhood.

She married John Corbin, an artilleryman in Captain Francis Proctor's First Company of the Pennsylvania Artillery, and followed him into war. When he was killed during the British assault on Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, she stepped into his place at the cannon. With grit and fury, she loaded, aimed, and fired, fighting off Hessian soldiers until three grapeshot tore into her chest, jaw, and left arm, disabling her(her wounds vary between historical accounts).

"Captured by the British and later released or paroled”, she eventually reappeared in the records as a member of the Corps of Invalids. Some Scholars state that the Corps of Invalids is when she earned the title "Captain Molly." Others have said it was because she wore a uniform and smoked a pipe.

An unverified statement from the 1915 Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society suggests that Margaret was paroled to General Greene and taken to Philadelphia along with other wounded soldiers. However, I have not found definitive documentary evidence to support this claim.

The Vanishing Act Nobody Documented

She vanished from the battlefield—but not from the story.

The aftermath of the battle was chaotic. Most American soldiers were captured and held on the field through Sunday, then marched to New York City under guard. As Hall documented in his book, there was one lone artillerist—likely a comrade of Margaret's—who escaped on a raft across the Hudson River and reported to General Nathanael Greene. According to historian Edward Hagaman Hall, although no official documents verify this, the letters between Gen. Greene and Gen. Washington indicate that the artillerist's account was Washington's first news from the north side of the fort, where Margaret had fought.

But Margaret? She vanishes from all official correspondence. According to Hall, Greene or Washington, does not mention her in the letters, nor was she listed among the known prisoners. As historian Edward Hagaman Hall wrote:

“What became of the unfortunate Margaret Corbin at this juncture does not appear.”

Although Hall's work is highly respected, the absence of conclusive documentary evidence for specific events in Corbin's life still calls for further investigation. I would love to find and examine the letters between Gen. Greene and Gen. Washington that historian Hall discusses in his book. Maybe there's something in the margin of those letters?

POW or Forgotten Hero?

The silence in the records may speak louder than facts.

One unverified account from the 1915 American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society suggests that Margaret was paroled to General Greene and sent to Philadelphia with the wounded. There's no documentation to confirm this, but it's plausible—especially given her later military record.

Eventually, she surfaces again—not as a camp follower, but as a soldier.

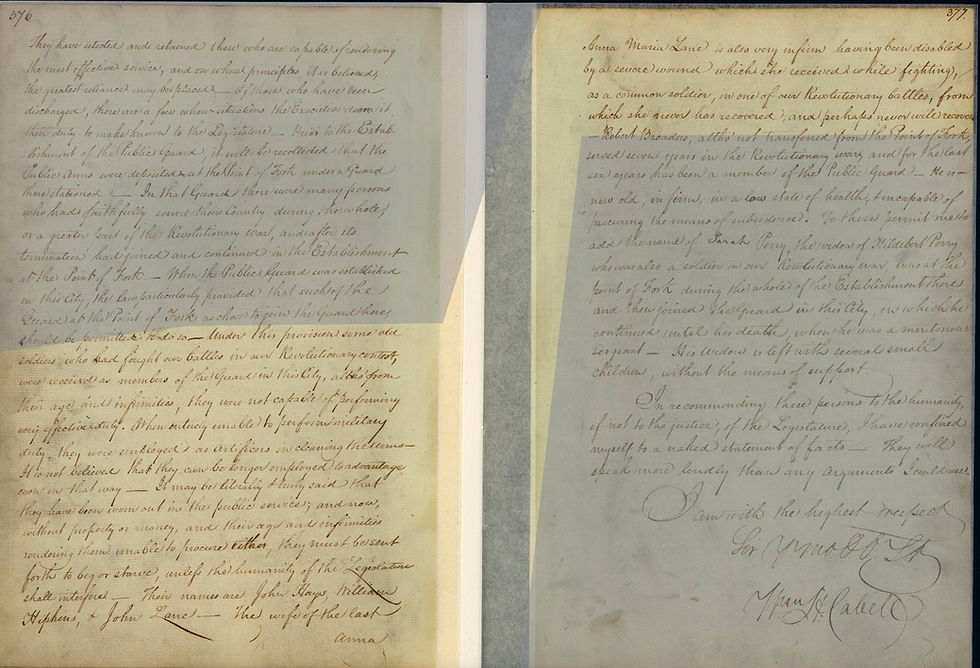

By 1779, Margaret Corbin was enrolled in the Pennsylvania Invalid Regiment, a unit created by Congress on June 23, 1777, to provide garrison service, act as a military school, and house soldiers unfit for field duty but still capable of service. She is listed in the Pennsylvania Archives as part of this regiment.

Rations, Whiskey, and Recognition

Her pension tells a story of both suffering and respect.

Margaret's injuries left her permanently disabled. The initial rations granted to her were inadequate, and on June 29, 1779, the Supreme Council of Pennsylvania voted for her $30 and urged further aid. Congress responded on July 6, 1779, by granting her:

A lifelong pension equal to half a soldier's pay,

A complete suite of clothing, or its cash equivalent.

She became the first woman in U.S. history to receive a military pension.

Still, even this was not enough. Later petitions noted that her condition remained dire, and yet she continued to receive military rations—including whiskey, a standard part of a soldier's provisions.

Why Would the Army Do That?

Because Margaret Corbin, a military wife, had proven herself in the most unthinkable way?

A woman firing a cannon didn't fit any military model of the time—not soldier, not civilian. Perhaps that's why her capture, injuries, or the possible escape occurred, and services were poorly documented. She didn't fit the system, so she slipped between its cracks (or better yet, she flowed into the margin and footnotes).

But her pension—and the rare privilege of enlistment in the Invalid Corps—proved that the Army saw her as one of their own.

Not just a widow.

Not just a woman.

But a soldier–– Patriot

Final thought: Whose Stories Get Remembered?

Margaret Corbin’s real legacy isn’t just what she did—but how easily it was almost lost.

Margaret Corbin didn't just fire a cannon—she broke barriers. Her story, fragmented as it is, challenges the conventional narratives of gender in military history. She blurred the lines between follower and fighter, supporter and soldier. Her recognition at West Point affirms the complexity of her role—and the magnitude of her courage. But her story also leaves us with more complicated questions:

Who gets remembered in war? Whose contributions are preserved? And who gets erased?

Thank you for reading this. Whether you leave a comment that is good, bad, or ugly, I appreciate that as well.

~Mel

#Margaret Corbin #AmericanRevolution #MilitaryWives #RevolutionaryWomen #Army250

References:

Biddle, Gertrude (Bosler), and Sarah Dickson Lowrie. Notable Women of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1942.

Clement, John, ed. Noble Deeds of American Women: With Biographical Sketches of Some of the More Prominent. Buffalo, NY: Orton & Co., 1858.

Egle, William Henry. Some Pennsylvania Women during the War of the Revolution. Harrisburg, PA: Harrisburg Publishing Company, 1898.

Hall, Edward Hagaman. Margaret Corbin, Heroine of the Battle of Fort Washington, 16 November 1776. New York: American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1932.

Hill, Steven. “More than Equal: Unlikely (s)Heroes of the Revolutionary War.” DemocracySOS, March 14, 2024. https://democracysos.substack.com/.

Jones, Thomas, and Edward Floyd de Lancey. History of New York during the Revolutionary War and of the Leading Events in the Other Colonies at That Period. New York: New York Historical Society, 1879.

Megan, Brett. “Margaret Cochrane Corbin and the Papers of the War Department.” The 18th-Century Common, October 20, 2014. http://www.18thcenturycommon.org/margaret-cochrane-corbin/.

Schenawolf, Harry. “Margaret Corbin: Manned the Cannon When Her Husband Fell at the Battle of Fort Washington.” Revolutionary War Journal, August 1, 2019. https://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/margaret-corbin-manned-the-cannon/.

Primary Sources:

Government and Institutional Records:

Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Volume XIV, 1779: April 23 – September 1. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789. Volume XVII, 1780: May 8 – September 6. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.

Papers of the Continental Congress. Volume 3, Folio 501–502, July 1779. Washington, D.C.: National Archives.

Minutes of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, From Its Organization to the Termination of the Revolution. Volume XII, May 21, 1779 – July 12, 1781. Harrisburg, PA: State Printer.

Digital Archives:

National Archives Foundation. “Revolutionary Women,” April 23, 2024.

Papers of the War Department, 1784–1800. “Forwarding of Ordnance & Stores Returns,” August 13, 1787.

Papers of the War Department, 1784–1800. “Report from West Point,” January 31, 1786.

Papers of the War Department, 1784–1800. Letterbook No. 1, West Point 1784–1786, entry dated January 31, 1786

Newspaper Article:

The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.). “Two ‘Mollys’ of Revolution Proved Distinct Heroines.” April 7, 1926.

Comments